Black Women in the Workforce and Tall Poppy Syndrome

February is Black History Month and with this, we want to highlight how Black people in Canada remain resilient against Canada’s historic discriminatory treatment towards them. For example, 1911 laws prohibited “immigrants belonging to any race deemed unsuited to the climate or requirements of Canada.” This regulation was further amended to include Black people, and although this policy did not become law, it does exemplify how Canada was not keen on increasing Black immigration. This month serves as a reminder that all Canadians have a role in facilitating positive change and being aware of our unconscious biases. That way, we can address and help remedy the disparities that Black Canadians face, especially when it comes to Black women in our workplaces. Black working women juggle the implicit and persistent forms of structural violence that Black Canadians face as well as the inequities associated with working women.

To understand the realities of working women in Canada, Dr. Rumeet Billan, PhD and CEO of Viewpoint Leadership, conducted a study on Tall Poppy Syndrome (TPS) and its effects. “Tall Poppy Syndrome” is a workplace phenomenon that primarily affects women in the workplace, harming their workplace morale, mental health, employee satisfaction, and employee retention. It derives its name from the tendency to cut down the “tallest poppy” in a group as women often face work environments where they feel undermined, criticized for their achievements, and inadequately acknowledged for their successes. Dr. Billan concluded that 87% of women in her study felt they were cut down, attacked, and/or resented by co-workers for their success. By actively supporting and recognizing workers, as well as providing training that focuses on bias-awareness and programs that aim to educate employees about gender-based differences, employers can counter assumptions that create inequalities in the workplace.

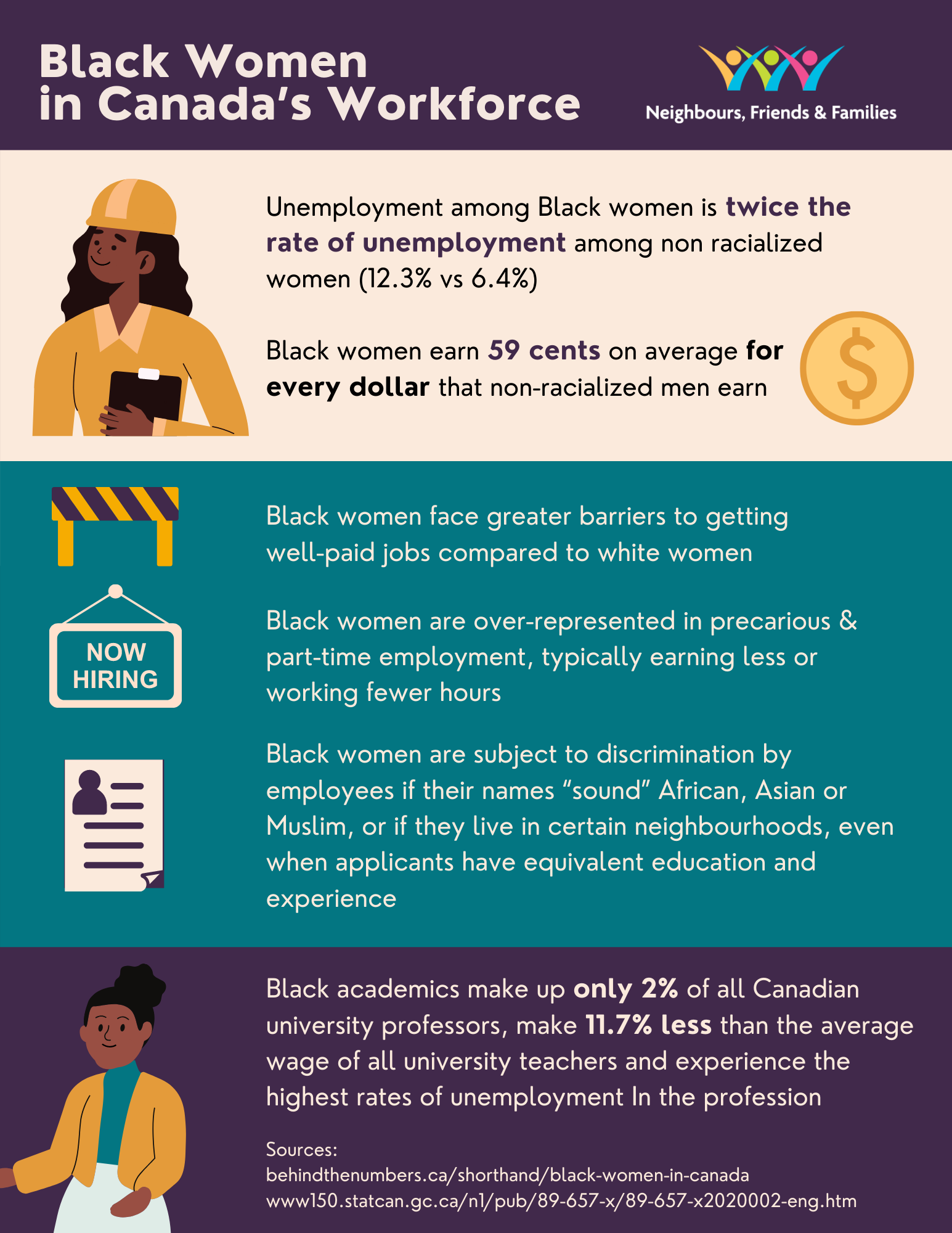

Black women further encounter conflicting labour market statistics. The Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives reported that the labour force participation rate of Black women was 66.1%, which is five percentage points higher that White women, yet their unemployment rate was twice the rate of White women. Furthermore, Black women’s earning gap was also significantly larger, as Black women earn 59 cents for every dollar a White man earns. These income differences reflect the deeper systematic issues and realities faced by Black working women. A Statistics Canada survey from November 2020 found that Black women face an unemployment rate of 12.5%, which was notably higher than the rest of the female population (6.6%). These statistics emphasize how Black women, despite their abilities and qualifications, still face the brunt of economic hardships in Canada. The comparison is not meant to polarize different demographic groups but to illustrate how unequal opportunities are actualized.

These issues of racial inequality were brought to the forefront of social and political discourse during this past summer’s Black Lives Matter movements. The reignited discussions about how ongoing discrimination against Black people amplified awareness of these issues, but the COVID pandemic exemplified exactly how these realities disempower them. COVID exacerbated the already-present inequalities in society, negatively impacting women more than men, and Black women most of all. The disparity is not only due to differences in jobs but issues of access, availability of affordable childcare options, and access to high-speed Internet. Furthermore, in a study conducted by René Houle, a senior analyst for Statistic Canada, he found that these gaps in employment persist even after the effects of various socioeconomic factors are controlled, Black people face challenges especially in terms of wages, poverty and employment. Black women were already discriminated against in the workforce, but they are now also overrepresented in frontline and lower-paid jobs at the highest risk of COVID exposure or most vulnerable to layoffs. These systemic inequalities affect the ability of Black women to find safe work and job security throughout the pandemic.

Racism in Canada is historic and sustained, which means that they need to be addressed and fixed. It is important to address and combat employment and work culture issues to ensure equal treatment of Black working women. The Employment Equity Act, a federal law that protects disadvantaged groups of society including women, people with disabilities, Indigenous people, and visible minorities, is a great start but it only applies to federally-regulated industries and covers only about 10% of the Canadian workforce. By further implementing equity programs and legislation, we can increase employment opportunities for Black Canadians and educate hiring managers to be cognizant of their unconscious biases.

Conscious efforts toward inclusion need to be made not just to fill diversity quotas, but also to fight against systemic racism and begin making real, measurable improvements to the inequality that Black women in this country have faced for decades. All Canadians can contribute, first and foremost, by looking inward. We need to realize the stereotypes and prejudices that we hold and educate ourselves on how systemic oppression is actualized. By listening to what minorities tell us about what they need, what they want and how to help them, and taking these demands seriously, we can build a universal work environment that better supports Black women across Canada.