Courage and Solidarity Brought Us Here

The astounding speed and force with which the #MeToo movement has entered popular discourse and consciousness can make it seem as if it was a spontaneous uprising. But the foundational work that exposed workplace sexual harassment and held space for the much needed change we are beginning to see has been going on for a long time.

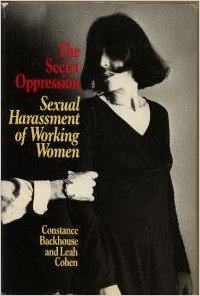

In 1979 Catherine MacKinnon wrote Sexual Harassment of Working Women in the U.S. and Constance Backhouse and Leah Cohen wrote The Secret Oppression: Sexual Harassment of Working Women in Canada. These first books about workplace sexual harassment were ground-breaking because they gave us language to describe distressing behaviours that had been happening in the workplace but which all too often were considered “part of the job.” Not having language to talk about a problem is a very effective strategy to make it invisible. The gift of language started us on a journey to the #MeToo movement.

We can point to some seminal events in the journey and the first to come to mind is the testimony of Anita Hill who described to a Senate panel in 1991 how her former supervisor, current Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, had sexually harassed her when she was a young assistant at the U.S. Department of Education's Office for Civil Rights. Although her testimony against Thomas is now seen as a watershed moment in the fight against sexual harassment in the workplace, at the time, her explosive allegations were doubted, exposing her to public mockery and humiliation. Although it has taken decades, Anita Hill is finally receiving the wide-spread recognition and respect that she so deserves for her brave actions and her ability to withstand the firestorm of controversy that overtook her life for so many years.

We have our Canadian heroes in this struggle as well. Bonnie Robichaud, a lead hand cleaner at the Air Defense Command Base in North Bay waged a seven-year battle from 1980 to 1987 after she was sexually harassed by her supervisor. Her case eventually ended up in the Supreme Court which ruled that under obligations set out in the Canadian Human Rights Act employers are responsible for maintaining a harassment free workplace, or as Bonnie has explained many times, they are responsible for sexual harassment, whether they know about it or not.

Yvonne Seguin, who experienced sexual harassment from her boss in her workplace in Montreal incorporated and became the Director of the Groupe d’aide et d’information sur le harcèlement sexuel au travail (The Group for aid and information on workplace sexual harassment) still the only Centre in Canada exclusively dedicated to assisting workers who have experienced sexual and other forms of workplace harassment.

Sharon Chapman won an 8-year civil suit against 3M after being sexually harassed and sexually assaulted in her workplace on a daily basis for 13 years. To this day, she claims her refusal to agree to a gag order, enabling her to speak freely about her case, as her primary victory.

Theresa Vince, a Human Resources Training Administrator and a twenty-five-year employee for Sears Canada Inc. was murdered at work on June 2, 1996 by her boss, the store manager, who also shot and killed himself. Sixteen months earlier she had made a complaint of sexual harassment and a poisoned work environment.

The Vince family poured their grief over the loss of a mother and a wife into social action. Supported by the Chatham Kent Sexual Assault Crisis Centre under the leadership of Michelle Schryer they collaborated with human rights lawyer Geri Sanson and then MPP for Chatham-Kent, Pat Hoy, to draft a private member’s bill that would make sexual harassment an occupational health and safety hazard. Treating sexual harassment as an occupational health and safety hazard would make employers responsible for addressing it immediately, as every worker has the right to a safe workplace. This vision of a mechanism that would provide an immediate remedy contrasted sharply with the existing remedy of filing a human rights complaint. Not only was it difficult to navigate the human rights complaint process at the time; the sad fact was that most women lost their jobs long before a complaint was heard, if it was heard at all.

It took a total of 7 private member’s bills, introduced by Pat Hoy and Liberal and NDP colleagues supported by women’s advocates and the labour movement before the Ontario Liberal Government took up the legislation and introduced Bill 168 in 2010, making harassment and violence, including domestic violence an occupational health and safety hazard.

Sharon Chapman and Jacquie Carr, one of Theresa’s daughters were among the first women in the province to provide training, support and advocacy for women undergoing sexual harassment experiences and complaints. Together and independently they provided emotional support and system navigation aid to hundreds of women and the occasional man.

Dr. Sandy Welsh, a Professor of Sociology and currently Vice-Provost, Students at the University of Toronto made important contributions to the understanding of sexual harassment and the intersectional nature of harassment through both academic research and collaboration with community-based partners.

In 2004 the Workplace Violence and Harassment Report detailed the personal experiences of women who have experienced workplace harassment and the context in which these experiences happened. An important finding of that research was the need to incorporate race and citizenship into the analysis of sexual harassment in order to understand how diverse groups of women define and experience the problem. The report concluded, as the #MeToo movement has today, that if we want to end the harassment, we must transform the inequality and discrimination that is woven into the fabric of so many workplace cultures. Sandy Welsh, Sharon Chapman and Jacquie Carr were all co-authors and major contributors to the report.

Ontario has continued to make legislative changes, adding a definition of sexual harassment to the Occupational Health and Safety Act and requiring that employers investigate complaints of sexual and other forms of harassment.

The Federal government is currently making changes to the Canada Labour Code, also focusing on harassment and violence in the workplace.

It has taken nearly 40 years, but the landscape has changed drastically. Legislation requires employers to have policies to prevent and respond to sexual harassment; employers are held responsible for ensuring that their workplaces are free from harassment – they can’t claim they didn’t know what was happening; those who have experienced sexual harassment are speaking out and finding strength and solidarity in numbers.

But let’s not lull ourselves into complacency. Even today those who break the silence often face a backlash. For all those women in precarious jobs or working in male dominated industries or who are isolated by a harasser or who are in industries where there is more anonymity and not the same level of public scrutiny, speaking out can mean a choice between telling your story and seeking justice or losing your job.

There are no simple answers or quick fixes to this unsettling reality. There is only the same courage and solidarity that has brought us to this point.

We can stand with Catherine MacKinnon who is, “inspired by the brilliance, heart, and grit of all the survivors who are speaking out and reflecting on their experiences of sexual violation, and being listened to.” [i]

And we can again look to Anita Hill for wisdom as she reminds survivors that, “… speaking out, despite the hardships, can be self-liberating and an inspiration to others” and reminds the rest of us, “Social justice, may not be your vocation — your job title may not say ‘Social Justice Crusader Around the World’ — but it can guide you in terms of how you treat your colleagues at work.”[ii]