The Power of Regret

Amber Wardell

Amber is the coordinator of the Haldimand & Norfolk Justice for Women Review Team and an abuse counsellor at Haldimand & Norfolk Women’s Services. She has worked for over a decade as a community educator, advocate, and counsellor for women and youth who have experienced sexual and domestic violence. Amber sits on the Advisory Committee of the Building a Bigger Wave Ontario Network and is a passionate advocate for feminism, equality, and LGBTQ2SI+ rights. A graduate of the University of Toronto, she has contributed to publications including the Varsity, the University of Toronto Undergraduate Journal of Sexual Diversity Studies and SOS magazine.

For a number of years I have been travelling to workplaces in my community to talk about intimate partner violence and how to recognize and respond to signs that a coworker might be experiencing abuse. After years of these presentations, what I remember the most, are the faces filled with regret that approach me afterwards. They tell me a story I have heard many times before; they once had a friend, coworker, neighbour, or family member who they were worried about. This person seemed to change over time and become more distant, irritable, anxious, and disconnected from the world around them. They didn’t know how to help the person they cared about and realize now they were trapped in an abusive relationship.

After just one hour of MIOB training they now know:

The person changed over time as they began to focus more and more on their partner’s thoughts, feelings, actions, and needs then on their own as a means of survival. In an attempt to predict and prevent escalations in violence she may become hyper aware of her partner’s moods and “walk on eggshells” in her own home. Any attempts at self care are likely to be categorized as selfish, and interests that are not shared with the abusive partner are discouraged.

The distance is caused by social and physical isolation; women experiencing abuse pull away due to shame, or feeling as though no one else can understand what they are going through. Abusive partners may actually stop her from seeing others, or use manipulation tactics such as guilt, to prevent her from spending time with friends and family who may encourage her to question the equality in her relationship. Both physically and emotionally removed from social circles, she may feel as though there is no way for her to reach out for help. In situations of coercive control, the abusive partner may track her whereabouts constantly; even 10 minutes spent chatting with a friend may lead to questioning about where she was and who she was with.

The irritability is caused by unexpressed, rational anger; when it is not safe to react to being hurt at home, feelings connected with the abuse may be expressed in more controlled environments, like the workplace.

The anxiety is caused by emotional, verbal, and psychological abuse. Survivors of intimate partner violence hear these types of belittling messages for years which eventually they believe: that they are not good enough, will never find another partner, cannot make it on their own, and no one will believe them. Feelings of intense fear during abusive incidents have conditioned the nervous system to overreact (and in some cases, underreact) to signs of danger causing their body to go into “panic mode” even in low risk situations. Even years after leaving an abusive relationship, a smell, sound, or image may trigger memories of an abusive incident and instantly leave the survivor feeling as though they are again being hurt. She may also be anxious as she is aware there is a threat to her emotional and physical health and in some cases her life.

Often the individuals who approach me following presentations are not sure what happened to the friend, neighbour, or coworker that was in an abusive relationship. They stopped trying to call or stop by because it was never a good time or one of them moved away or changed workplaces.

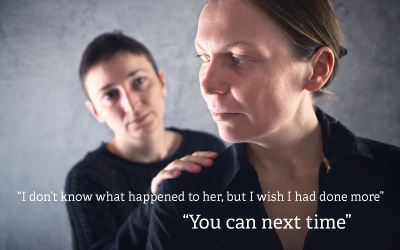

“I don’t know what happened to her, but I wish I had done more” they say. “You can next time” I tell them.

We both know they will. The regret I saw has changed to hope. Hope that next time they can reach out and make a difference in the life of someone they care for.